New Year of H’Mong People

Tue, 31 Mar 2015 . Last updated Thu, 25 Jun 2015 09:04

-

Vietnam – The S-shaped country 10092 viewed

Vietnam – The S-shaped country 10092 viewed -

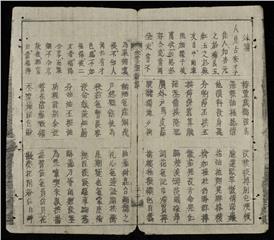

Ancient Vietnamese coins – Episode 1 9425 viewed

Ancient Vietnamese coins – Episode 1 9425 viewed -

Special cultural features of Quan Ho singing 8586 viewed

Special cultural features of Quan Ho singing 8586 viewed -

Ancient Vietnamese coins – Episode 2 8399 viewed

Ancient Vietnamese coins – Episode 2 8399 viewed -

Vietnam History 1858-1945 7168 viewed

Vietnam History 1858-1945 7168 viewed -

The Vietnamese Proclamation of Independence 6690 viewed

The Vietnamese Proclamation of Independence 6690 viewed -

Cham Muslims in An Giang 6123 viewed

Cham Muslims in An Giang 6123 viewed -

Vietnam history 1945-1954 6002 viewed

Vietnam history 1945-1954 6002 viewed -

Predestined love tie with Ao Dai - Vietnamese long dress 5706 viewed

Predestined love tie with Ao Dai - Vietnamese long dress 5706 viewed

Located in Moc Chau district about 40km from the town center, Ta Phinh village is known as the land of fog. Fog is considered a specialty of this place. When New Year of H’Mong people comes, the village is covered with colorful peach and plum blossoms.

H’Mong people word hard around the year like bees of the mountain. They sow the seeds of corn in the mountain soil. Life of H’Mong people is measured by the number of corn crops. When the H’Mong women stop their work on the field to prepare for the New Year, Vang A Lu leaves school for his homevillage to celebrate the traditional festival of his people.

The rain in the last day of the year does not discourage this H’mong guy. He grew up this village and has celebrated 20 Tet of H’mong people. He knows this is the most important festival in the year for H’Mong people. The New Year Festival of H’Mong takes place a month earlier than the Lunar New Year, from November 30 to the middle of December in the lunar calendar, depending on each family and village.

Tet is knocking on the door of every H’Mong family. By the fire, the women in Vang A Lu’s family are preparing for the major festival. With Kinh people, “chung” cake and “day” are the symbols of Tet, of the Heaven and the Earth. As for H’mong people, the “giay” cake is the symbol of love and loyalty. It also symbolizes the Moon and the Sun - the origin of humans and all creatures. The mortar is made from a solid trunk with smooth grain and fragrant smell. Pounding flour requires strength, thus strong young men often take on this task. Only H’Mong people can make such smooth flour. The longer the rice is pounded, the smoother the flour is. These children are eager for Tet.

H’Mong people think all the things in the family, especially the farming tools, have souls. The help them have bumper crops so that they have food and their children can go to school. Tet is the only occasion the people and tools can have a rest. H’Mong people often stick a piece of paper on each of these tools as a way to give thanks to them and to pray for a new bumper crop. With H’mong people, the New Year is marked by the first cock-crow. Each family will make important rituals in the New Year on different days.

The Tet atmosphere is now felt everywhere in the village. All the families are buzzing with activity. The sound of rice pounding echoes over the village. “Day” cakes are indispensable during the New Year Festival of H’Mong people. The cakes made from “nuong” sticky rice grown on the hills. They are offered to the ancestors after a bumper crop. H’mong people invite each other to enjoy “day” cakes during the New Year. These people have worked hard all year round in the fields. Tet is an opportunity for them to rest before a new crop. This corn crop succeeds that crop. Several young men are killing the pig to make a festal meal according to the tradition of H’mong people.

Lu’s father is preparing necessary rituals. The men in the family cut the bamboo blade to sweep the floor to dispel all the bad luck in the previous year. During the 3 days of Tet, they do not sweep the floor. H’Mong people worship the God of House, it is called “xu cang” in the H’Mong language. Any H’mong person who settles down to married life must have a “xu cang”. They wear the new cloth for “xu cang” once every year by replacing the old piece of paper with the new one. They use a rooster as an offering to “xu cang”, showing their respect for the god. After cutting the roaster’s throat, the house owner plucks 3 bits of neck feathers and sticks them on the upper part of the paper. “Xu cang” is considered as the guardian in the thought of H’Mong people. Therefore, H’Mong people attach great importance to worship of “xu cang”.

Generations of H’mong people succeed each other, working and resting, diligence and generosity. The feast at Vang A Lu’s house is an opportunity for all the family members to gather together. They eat and drink until getting drunk. H’Mong people do not eat vegetables during three Tet days. They think that spring is the season of growth. If they eat vegetable, the weeds will grow in the fields and they cannot have a well-off life in the next year.

When adults are offering corn wine to each other, the kids call each other to go out for a walk. They gather in groups and chat noisily and play “nem pao” (ball throwing). H’Mong boys and girls call each other to go out for celebration. The “pao” has helped many boys and girls of H’Mong ethnic group become husbands and wives. The “pao” is passed to and fro among the boys and the girls. They send love through their eyes and smiles in the rhythm of the “pao”. “I threw the “pao”, you did not catch. You don’t love me; the “pao” fell on the ground. Who do you choose, which “pao” do you catch?

Just like that, the “pao” brings the people to each other, forming a circle of existence from generation to generation. H’Mong girls are good at throwing “pao” and H’mong boys are good at playing “cu” (humming top). The age of a H’Mong boy is calculated by the size of the “cu” as every year he makes a new and bigger “cu” to fit his first. Its shape is unchanged but its size differs.

Playing “cu” or “tau thu lau” in H’Mong language helps the boys have firm arms, enduring strength and good judgment. Many girls fall in love with the winners in “cu” competitions. And not a few many of whom have got married. The atmosphere is full of the aroma of corn wine. H’Mong men are playing “khen” (pan flute). The sound of “khen” echoes touching the rocks, touching the people’s heart. The tinkling coins mix with the joy of heaven and earth. Spring comes in the yellow murtard plots in front of the house.

The boys and girls fall in love with each other. “Khen” and bamboo flutes are close friends of any H’mong person from birth to death. Their sound lulls them to sleep during the childhood, follows them to field and to such festivals. The sound follows them in their belief in a prosperous new year.

Source: VTC10 - NETVIET