Vietnamese grammar is not easy to be absorbed, though writing system based on Latin alphabet. It is an independent language in South East Asia. Grammatical relations are expressed without the morphology; it is reflexed via vocabularies and orders.

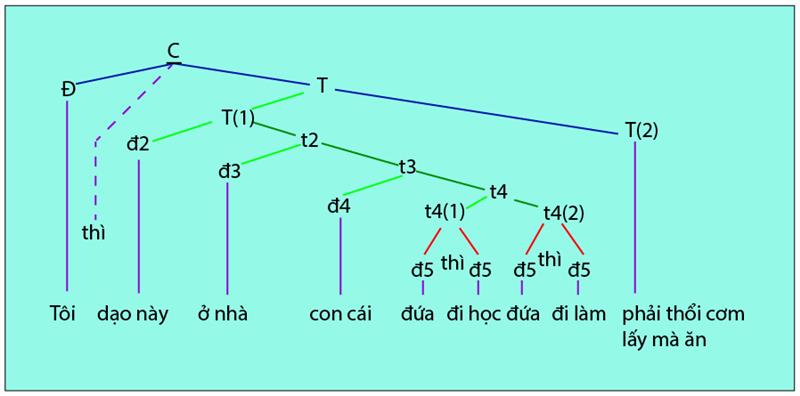

Like many languages in Southeast Asia, Vietnamese language is an isolating language. Vietnamese does not use morphological marking of case, gender, number or tense (and, as a result, has no finite/nonfinite distinction). Also like other languages in the region, Vietnamese syntax conforms to subject–verb–object word order, is head-initial (displaying modified-modifier ordering), and has a noun classifier system. Additionally, it is pro-drop, wh-in-situ, and allows verb serialization. Vietnamese grammar is characteristics of Vietnamese language in accordance with part of speech, word structure, and sentence.

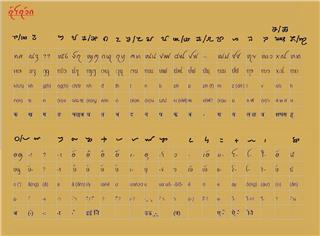

By late 19th century, Vietnamese writing system based on Chinese characters widely used in Vietnam. Yet, all formal writings, including important document of the state, scholarship and formal literature were done in Literary Chines. Folk literature in Vietnamese was kept by the characters of Nom. Vietnamese people borrowed many Chinese characters which were modified and invented to represent native Vietnamese words to use for the Nom script. Formed in the 13th century, even earlier, the Nom characters reached its zenith in the 18th century when it was widely used in Vietnamese works of literature and poetry. However, it was only used for official purposes during the brief Ho and Tay Son dynasties. After that, all Chinese writing system, Confucianism and other influences of Chinese were eliminated from Vietnam, especially the Nom script by French colonialism’s administration.

In the 17th century, Vietnam language was systematized by the French Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1660), based on works of earlier Portuguese missionaries. The Vietnamese alphabet (literally national language) was gradually expanded from its initial domain in Christian writing to become more popular. However, not until the beginning of the 20th century did Romanized script come to predominate. Then, education became widespread and a simpler with the new writing system which was more appropriated for teaching and communication with the general population. Under French colonialism, French antiquated Chinese in administration. All public documents were written by the Latin alphabet in 1910 by issue of a decree by the French Résident Supérieur of the protectorate of Tonkin. By the middle of the 20th century, essentially all writing was done in this new Vietnamese alphabet, which became the official script on independence. “Nho” characters were still used on early North Vietnamese and late French Indochinese banknotes issued after World War II, but fell out of official use shortly thereafter. Today, only a few scholars and extremely elderly people are able to read “Nom” scripts.

Between 1954 and 1974, the script of French scholars and rulers was changed through conferences after independence. The Central Vietnamese dialects were also reflected through the script, in which vowels and final consonants of Central Vietnamese are most similar to that of northern dialects and initial consonants most similar to those in southern dialects. This Central Vietnamese is apparently close to the northern Vietnamese in Hanoi spoken sometime after 1600 but before the present. (This is not unlike how English orthography is based on the Chancery Standard of late Middle English, with many spellings retained even after significant phonetic change.)

Beside the distinct linguistic features of Vietnamese language, word play is another unique character in complex Vietnamese grammar. A word play or a language game is a way of changing the order of words in a phrase, or changing the order of consonants in words, or uttering these words in different ways to change or create a new phrase with new meanings, even nonsense words. This game contributes in softening some sensitive issues in life, implying another meaning in those words. By virtue of these above-mentioned features, Vietnamese language is a demanding language for those who adore studying more about it.